Battle of Arsuf

| Battle of Arsuf | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Third Crusade | |||||||||

19th-century depiction of the battle by French painter Éloi Firmin Féron (1802–1876) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Angevin Empire Kingdom of France Kingdom of Jerusalem Knights Hospitaller Knights Templar Contingents from other states | Ayyubid Sultanate | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Richard I, King of England Hugh III, Duke of Burgundy Guy of Lusignan Garnier de Nablus Robert IV of Sablé James of Avesnes † Henry II, Count of Champagne |

Saladin Saphadin Al-Afdal ibn Saladin Aladdin of Mosul Musek, Grand Emir of the Kurds † Al-Muzaffar Taqi al-Din Umar | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

11,200 (total)[2][3]

| 25,000 cavalry[2] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| c. 700 killed (est.)[4] (Itinerarium) | c. 7,000 killed (est.)[5] (Itinerarium) | ||||||||

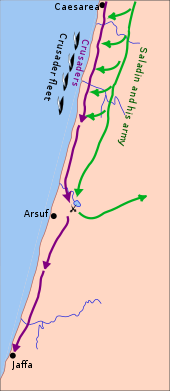

The Battle of Arsuf took place on 7 September 1191, as part of the Third Crusade. It saw a multi-national force of Crusaders, led by Richard I of England, defeat a significantly larger army of the Ayyubid Sultanate, led by Saladin.

Following the Crusaders' capture of Acre, Saladin moved to intercept Richard's advancing army just outside of the city of Arsuf (Arsur in Latin) as it moved along the coast from Acre towards Jaffa. In an attempt to disrupt the cohesion of the Crusader army as they mobilized, the Ayyubid force launched a series of harassing attacks that were ultimately unsuccessful at breaking their formation. As the Crusaders crossed the plain to the north of Arsuf, Saladin committed the whole of his army to a pitched battle. The Crusader army maintained a defensive formation as it marched, with Richard awaiting the ideal moment to mount a counterattack. However, after the Knights Hospitaller launched a charge at the Ayyubids, Richard was forced to commit his entire force to support the attack. The Crusader charge broke the Ayyubid army; Richard was able to restrain his cavalry from a rash pursuit, regrouping them to achieve victory.

Following the engagement, the Crusaders secured control over the central coast of Palestine, including the city of Jaffa.

Prelude: south from Acre

[edit]

Following the capture of Acre in 1191, Richard was aware that he needed to capture the port of Jaffa, before making an attempt on Jerusalem. Richard began to march down the coast from Acre towards Jaffa in August. Saladin, whose main objective was to prevent the recapture of Jerusalem, mobilised his army to attempt to stop the Crusaders' advance. Richard organised the advance with attention to detail. A large part of the Egyptian fleet had been captured at the fall of Acre, and with no threat from this quarter he could march south along the coast with the sea always protecting his right flank.[6] Saladin had destroyed (slighted) Jaffa's fortifications in the summer of 1190 due to its potential importance to the Crusaders.[7]

Mindful of the lessons of the disaster at Hattin, Richard knew that his army's greatest need was water and that heat exhaustion was its greatest danger. Although pressed for time he proceeded at a relatively slow pace. He marched his army only in the morning before the heat of the day, making frequent rest stops, always beside sources of water. The fleet sailed down the coast in close support, a source of supplies and a refuge for the wounded. Aware of the ever-present danger of enemy raiders and the possibility of hit-and-run attacks, he kept the column in tight formation with a core of twelve mounted regiments, each with a hundred knights. The infantry marched on the landward flank, covering the flanks of the horsemen and affording them some protection from missiles. The outermost ranks of the infantry were composed of crossbowmen. On the seaward side was the baggage and also units of infantry being rested from the continuous harassment inflicted by Saladin's forces. Richard wisely rotated his infantry units to keep them relatively fresh.[8][9]

Though provoked and tormented by the skirmish tactics of Saladin's archers, Richard's generalship ensured that order and discipline were maintained under the most difficult of circumstances.[10] Baha al-Din ibn Shaddad, the Muslim chronicler and eyewitness, describes the march:

"The Moslems discharged arrows at them from all sides to annoy them, and force them to charge: but in this they were unsuccessful. These men exercised wonderful self-control; they went on their way without any hurry, whilst their ships followed their line of march along the coast, and in this manner they reached their halting-place."[11]

Baha al-Din also described the difference in power between the Crusader crossbow and the bows of his own army. He saw Frankish infantrymen with from one to ten arrows sticking from their armoured backs marching along with no apparent hurt, whilst the crossbows struck down both horse and man amongst the Muslims.[12]

Saladin's strategy

[edit]

The Crusader army's pace was dictated by the infantry and baggage train; the Ayyubid army, being largely mounted, had the advantage of superior mobility.[13] Efforts to burn crops and deny the countryside to the Frankish army were largely ineffective as it could be continuously provisioned from the fleet, which moved south parallel with it. On 25 August the Crusader rearguard was crossing a defile when it was almost cut off. However, the Crusaders closed up so speedily that the Muslim soldiery was forced to flee. From 26 to 29 August Richard's army had a respite from attack because while it hugged the coast and had gone round the shoulder of Mount Carmel, Saladin's army had struck across country. Saladin arrived in the vicinity of Caesarea before the Crusaders, who were on a longer road. From 30 August to 7 September Saladin was always within striking distance, and waiting for an opportunity to attack if the Crusaders exposed themselves.[14][15]

By early September, Saladin had realised that harassing the Frankish army with a limited portion of his troops was not going to stop its advance. In order to do this he needed to commit his entire army to a serious attack. Fortuitously for Saladin, the Crusaders had to traverse one of the few forested regions of Palestine, the "Wood of Arsuf", which ran parallel to the sea shore for more than 20 km (12 mi). The woodland would mask the disposition of his army and allow a sudden attack to be launched.[16][17][18]

The Crusaders traversed half of the forest with little incident, and they rested on 6 September with their camp protected by the marsh lying inland of the mouth of the river Nahr-el-Falaik, called by them Rochetaillée. To the south of the camp, in the 10 km (6 mi) the Crusaders needed to march before gaining the ruins of Arsuf, the forest receded inland to create a narrow plain 1.5–3 km (1–2 mi) wide between wooded hills and the sea. This is where Saladin intended to make his decisive attack. While threatening and skirmishing along the whole length of the Crusader column, Saladin reserved his most sustained direct assault for its rear. His plan appears to have been to allow the Frankish van and centre to proceed, in the hope that a fatal gap might be created between them and the more heavily engaged rearmost units. Into such a gap Saladin would have thrown his reserves in order to defeat the Crusaders in detail.[19]

Battle

[edit]Estimation of the size of the opposing armies

[edit]The Itinerarium Regis Ricardi implies that the Ayyubid army outnumbered the Crusaders three-to-one. However, unrealistically inflated numbers, of 300,000 and 100,000 respectively, are described.[20] Modern estimates of Saladin's army place it at around 25,000 soldiers, almost all cavalry (horse archers, light cavalry, and a minority of heavy cavalry).[21] Based on the number of soldiers that the three kings brought to the Holy Land, as well as what troops the Kingdom of Jerusalem could muster, McLynn calculates the total Crusader forces at Arsuf as numbering 20,000: 9,000 troops brought by Richard from his dominions, 7,000 French troops left by Phillip, 2,000 troops from Outremer, and 2,000 more soldiers from every other source (Danes, Frisians, Genoese, Pisans, Turcopoles). Boas notes that this calculation doesn't account for losses in earlier battles or desertions, but that it is probable that the Crusader army had 10,000 men and perhaps more.[22] The Cambridge Illustrated Atlas of Warfare lists Richard's army as possessing 10,000 infantry (including spearmen and crossbowmen) and 1,200 heavy cavalry, with Saladin's army possessing twice as many men with a preponderance of cavalry.[23]

Organisation and deployment

[edit]

At dawn on 7 September, as Richard's forces began moving out of camp enemy scouts were visible in all directions, hinting that Saladin's whole army lay hidden in the woodland. King Richard took especial pains over the disposition of his army. The probable posts of greatest danger, at the front and especially the rear of the column, were given to the military orders. They had the most experience of fighting in the East, were arguably the most disciplined, and were the only formations which included Turcopole cavalry who fought like the Turkish horse archers of the Ayyubid army.[24]

The vanguard of the Crusader army consisted of the Knights Templar under Robert de Sablé. They were followed by three units composed of Richard's own subjects, the Angevins and Bretons, then the Poitevins including Guy of Lusignan, titular King of Jerusalem, and lastly the English and Normans who had charge of the great standard mounted on its waggon. The next seven corps were made up of the French, the Flemings, the barons of Outremer and small contingents of crusaders from other lands. Forming the rearguard were the Knights Hospitaller led by Garnier de Nablus. The twelve corps were organised into five larger formations, though their precise distribution is unknown. Additionally, a small troop, under the leadership of Henry II of Champagne, was detached to scout towards the hills, and a squadron of picked knights under King Richard and Hugh of Burgundy, the leader of the French contingent, was detailed to ride up and down the column checking on Saladin's movements and ensuring that their own ranks were kept in order.[25][26]

The first Saracen attack did not come until all the crusaders had left their camp and were moving towards Arsuf. The Ayyubid army then burst out of the woodland. The front of the army was composed of dense swarms of skirmishers, both horse and foot, Bedouin, Sudanese archers and the lighter types of Turkish horse archers. Behind these were the ordered squadrons of armoured heavy cavalry: Saladin's mamluks (also termed ghulams), Kurdish troops, and the contingents of the emirs and princes of Egypt, Syria and Mesopotamia. The army was divided into three parts, left and right wings and centre. Saladin directed his army from beneath his banners, surrounded by his bodyguard and accompanied by his kettle-drummers.[27]

Saladin's attack

[edit]

In an attempt to destroy the cohesion of the Crusader army and unsettle their resolve, the Ayyubid onslaught was accompanied by the clashing of cymbals and gongs, trumpets blowing and men screaming war-cries.[28]

"In truth, our people, so few in number, were hemmed in by the multitudes of the Saracens, that they had no means of escape, if they tried; neither did they seem to have valour sufficient to withstand so many foes, nay, they were shut in, like a flock of sheep in the jaws of wolves, with nothing but the sky above, and the enemy all around them."[29]

The repeated Ayyubid harrying attacks followed the same pattern: the Bedouin and Nubians on foot launched arrows and javelins into the enemy lines, before parting to allow the mounted archers to advance, attack and wheel off, a well-practiced technique. Crusader crossbowmen responded, when this was possible, although the chief task among the Crusaders was simply to preserve their ranks in the face of sustained provocation. When the incessant attacks of skirmishers failed to have the desired effect, the weight of the attack was switched to the rear of the Crusader column, with the Hospitallers coming under the greatest pressure.[30] Here the right wing of the Ayyubid army made a desperate attack on the squadron of Hospitaller knights and the infantry corps covering them. The Hospitallers could be attacked from both their rear and flank. Many of the Hospitaller infantry had to walk backwards in order to keep their faces, and shields, to the enemy.[31] Saladin, eager to urge his soldiers into closer combat, personally entered the fray, accompanied by two pages leading spare horses. Sayf al-Din (Saphadin), Saladin's brother, was also engaged in actively encouraging the troops; both brothers were thus exposing themselves to considerable danger from crossbow fire.[32][33]

Hospitallers break formation and charge

[edit]All Saladin's best efforts could not dislocate the Crusader column, or halt its advance in the direction of Arsuf. Richard was determined to hold his army together, forcing the enemy to exhaust themselves in repeated charges, with the intention of holding his knights for a concentrated counter-attack at just the right moment. There were risks in this, because the army was not only marching under severe enemy provocation, but the troops were suffering from heat and thirst. Just as serious the Saracens were killing so many horses that some of Richard's own knights began to wonder if a counter-strike would be possible. Many of the unhorsed knights joined the infantry.[34][35]

Just as the vanguard entered Arsuf in the middle of the afternoon, the Hospitaller crossbowmen to the rear were having to load and shoot walking backwards. Inevitably they lost cohesion, and the enemy was quick to take advantage of this opportunity, moving into any gap wielding their swords and maces. For the Crusaders, the Battle of Arsuf had now entered a critical stage. Garnier de Nablus repeatedly pleaded with Richard to be allowed to attack. He was refused, the Master was ordered to maintain position and await the signal for a general assault, six clear trumpet blasts. Richard knew that the charge of his knights needed to be reserved until the Ayyubid army was fully committed, closely engaged, and the Saracens' horses had begun to tire.[34] Whether through a lack of discipline or acting on Richard’s delegated authority, the Order’s marshal and one of Richard’s household knights, Baldwin le Carron, moved through their own infantry and charged into the Saracen ranks with a cry of “St. George!”; they were then followed by the rest of the Hospitaller knights.[36][30][37] Moved by this example, the French knights of the corps immediately preceding the Hospitallers also charged.[38]

The traditionally accepted version of events is that Garnier de Nablus and the Hospitaller cavalry charged when goaded beyond endurance, and did so in direct disobedience of Richard's orders. However, this version has been challenged. The established viewpoint draws on two related sources which do not match some other accounts, including Richard’s own letters on the battle. Recently, it has been proposed that Richard may have devolved authority to trusted subordinates to spot and seize any opportune moment to order a charge. Indeed, it is not clear how a trumpet signal would be heard amidst the clashing cymbals and gongs of the Ayyubid army or distinguished from Saladin’s own regular trumpet blasts.[39]

Crusader counterattack

[edit]

If the action of the Hospitallers constituted a breach of discipline, it could have caused Richard's whole strategy to unravel. Alternatively, he may have given Baldwin le Carron freedom to act on his own initiative in order to take advantage of a fleeting opportunity.[40] Either way, Richard recognised that the counterattack, once started, had to be supported by all his army and ordered the signal for a general charge to be sounded. Unsupported, the Hospitallers and the other rear units involved in the initial breakout would have been overwhelmed by the superior numbers of the enemy.[41] The Frankish infantry opened gaps in their ranks for the knights to pass through and the attack naturally developed in echelon from the rear to the van. To the soldiers of Saladin's army, as Baha al-Din noted, the sudden change from passivity to ferocious activity on the part of the Crusaders was disconcerting, and appeared to be the result of a preconceived plan.[42]

Having already been engaged in close combat with the rear of the Crusader column, the right wing of the Ayyubid army was in compact formation and too close to their enemy to avoid the full impact of the charge. Indeed, some of the cavalry of this wing had dismounted in order to loose their arrows more effectively.[43] As a result, the Ayyubids suffered great numbers of casualties, the knights taking a bloody revenge for all they had had to endure earlier in the battle. Baldwin le Carron and the marshal of the Hospitallers had chosen their moment well. Baha al-Din noted that "the rout was complete." He had been in the centre division of Saladin's army, when it turned in flight he looked to join the left wing, but found that it also was in rapid flight. Noting the disintegration of the right wing he finally sought Saladin's personal banners, but found only seventeen members of the bodyguard and a lone drummer still with them.[44][45]

Being aware that an over-rash pursuit was the greatest danger when fighting armies trained in the fluid tactics of the Turks, Richard halted the charge after about 1.5 km (1 mi) had been covered. The right flank Crusader units (including the English and Normans), which had formed the van of the column, had not yet been heavily engaged in close combat. They constituted a ready-made reserve, on which the rest regrouped. Freed from the pressure of being actively pursued, many of the Ayyubid troops turned to cut down those of the knights who had unwisely drawn ahead of the rest. James d'Avesnes, the commander of one of the Franco-Flemish units, was the most prominent of those killed in this episode. Amongst the Ayyubid leaders who rallied quickly and returned to the fight was Taqi al-Din, Saladin's nephew. He led 700 men of the Sultan's own bodyguard against Richard's left flank. Once their squadrons were back in order, Richard led his knights in a second charge and the forces of Saladin broke once again.[46][43]

Leading by example, Richard was in the heart of the fighting, as the Itinerarium describes:

There the king, the fierce, the extraordinary king, cut down the Turks in every direction, and none could escape the force of his arm, for wherever he turned, brandishing his sword, he carved a wide path for himself: and as he advanced and gave repeated strokes with his sword, cutting them down like a reaper with his sickle, the rest, warned by the sight of the dying, gave him more ample space, for the corpses of the dead Turks which lay on the face of the earth extended over half a mile.[47]

Alert to the danger presented to his scattered ranks, Richard, prudent as ever, halted and regrouped his forces once more after a further pursuit. The Ayyubid cavalry turned once again, showing they still had stomach to renew the fight. However, a third and final charge caused them to scatter into the woodland where they dispersed into the hills in all directions, showing no inclination to continue the conflict. Richard led his cavalry back to Arsuf where the infantry had pitched camp. During the night the Saracen dead were looted.[48]

Aftermath

[edit]

As always with medieval battles, losses are difficult to assess with any precision. The Christian chroniclers claim that Saladin's force lost 32 emirs and 7,000 men, but it is possible that the true number may have been fewer. Ambroise mentions that Richard's troops counted several thousand bodies of dead Saracen soldiers on the field of battle after the rout. Baha al-Din records only three deaths amongst the leaders of the Ayyubid army: Musek, Grand-Emir of the Kurds, Kaimaz el Adeli and Lighush. King Richard's own dead are said to have numbered no more than 700. The only Crusader leader of note to die in the battle was James d'Avesnes; a French knight of whom Ambroise made the claim that he cut down 15 Saracen cavalrymen before being killed.[49][50][51]

Arsuf was an important victory. The Ayyubid army was not destroyed, despite the considerable casualties it suffered, but it did rout; this was considered shameful by the Muslims and boosted the morale of the Crusaders. A contemporary opinion stated that, had Richard been able to choose the moment to unleash his knights, rather than having to react to the actions of an insubordinate unit commander, the Crusader victory might have been much more effective. Possibly being so complete a victory that it would have disabled Saladin's forces for a long time.[52][50] After the rout Saladin was able to regroup and attempted to resume his skirmishing method of warfare but to little effect; shaken by the Crusaders' sudden and devastatingly effective counterattack at Arsuf, he was no longer willing to risk a further full-scale attack. Arsuf had dented Saladin's reputation as an invincible warrior, and proved Richard's courage as a soldier and his skill as a commander. Richard was able to take, defend and hold Jaffa – a strategically crucial move toward securing Jerusalem. Also Saladin had to evacuate and demolish most of the fortresses of southern Palestine: Ascalon, Gaza, Blanche-Garde, Lydda and Ramleh, as he realised he could not hold them. Richard took the fortress of Darum, the sole fortress that Saladin had garrisoned, with only his own household troops, so low had Saracen morale been reduced. By depriving Saladin of the coast, Richard seriously threatened Saladin's hold on Jerusalem.[53][54] Richard spent time at Jaffa to rebuild the fortifications that Saladin had pre-emptively destroyed in the summer of 1190 in anticipation that the city would be useful to the Crusaders.[7]

Although the Third Crusade, in the end, failed to retake Jerusalem, a three-year truce was eventually negotiated with Saladin. The truce, known as the Treaty of Jaffa, ensured that Christian pilgrims from the west would once again be allowed to visit Jerusalem. Saladin also recognised the Crusaders' control of the Levantine coast as far south as Jaffa. Both sides had become exhausted by the struggle, Richard needed to return to Europe in order to protect his patrimony from the aggression of Philip of France, and Palestine was in a ruinous state.[55]

References

[edit]- ^ Claster, Jill N. Sacred Violence: The European Crusades to the Middle East, 1095–1396. University of Toronto Press, 2009. p. 207: "On September 7, just north of Arsuf, Richard and Saladin met in a pitched battle, the first time they fought face-to-face. The Muslims were not able to withstand Richard's mounted knights, and he won a decisive victory."

- ^ a b Boas, p. 78

- ^ Bennett, p. 101.

- ^ a tenth or a hundredth of the Ayyubid casualties, according to the Itinerarium (trans. 2001 Archived 9 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine Book IV Ch. XIX, p. 185)

- ^ 7,000 dead according to the Itinerarium trans. 2001 Archived 9 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine Book IV Ch. XIX, p. 185

- ^ Gillingham, p. 187

- ^ a b Möhring, p. 213

- ^ Oman, pp. 309–310

- ^ Verbruggen, p. 234.

- ^ Nicholson, p. 241.

- ^ Baha al-Din, Part II Ch. CXVII, p. 283.

- ^ Oman, p. 309

- ^ Gillingham, p. 186.

- ^ Oman, p. 308.

- ^ Verbruggen, p. 235.

- ^ Oman, pp. 310–311.

- ^ Gillingham, p. 188.

- ^ Verbruggen, pp. 235–236.

- ^ Oman, p. 312.

- ^ Anonymous translation of Itinerarium, Book IV Ch. XVI, p. 175

- ^ Boas, p. 78.

- ^ Boas, Adrian. "The Crusader World." 2015. p. 78. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Bennett, Matthew. The Cambridge Illustrated Atlas of Warfare: The Middle Ages, 768–1487. Vol 1. 1996. p. 101. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Oman, p. 307.

- ^ Oman, pp. 311–312.

- ^ Verbruggen, p. 236.

- ^ Oman, p. 312.

- ^ Gillingham, p. 189.

- ^ Anonymous translation of Itinerarium, Book IV Ch. XVIII, p. 178.

- ^ a b Verbruggen, p. 237.

- ^ Oman, p. 313.

- ^ Baha al-Din, Part II Ch. CXXII, p. 290.

- ^ Oman, pp. 313–314.

- ^ a b Gillingham, p. 189

- ^ Verbruggen, pp. 236–237.

- ^ Itinerarium, Book VI Ch. IV, pp. 251–252.

- ^ Bennett, 'Elite Participation', pp. 174–78.

- ^ Oman, p. 314.

- ^ Bennett, 'The Battle of Arsuf', pp. 49–50.

- ^ Bennett, 'The Battle of Arsuf', p. 50.

- ^ Gillingham, p. 190.

- ^ Oman, p. 315

- ^ a b Verbruggen, p. 238.

- ^ Baha al-Din, Part II Ch. CXXII, p. 291.

- ^ Oman, pp. 315–316

- ^ Oman, p. 316

- ^ Anonymous translation of Itinerarium, Book IV Ch. XIX, p. 182.

- ^ Oman, pp. 316–317

- ^ Baha al-Din, Part II Ch. CXXII, p. 292

- ^ a b Oman, p. 317

- ^ Ambroise, pp. 121–122

- ^ Anonymous translation of Itinerarium Book IV Ch. XIX, pp. 180–181

- ^ Oman, pp. 317–318

- ^ Verbruggen, p. 239.

- ^ Runciman, pp. 72–73

Bibliography

[edit]Primary sources

[edit]- Ambroise, The History of the Holy War, translated by Marianne Ailes, Boydell Press, 2003.

- Itinerarium Regis Ricardi Anonymous translation of Itinerarium Regis Ricardi, trans. In parentheses Publications, Cambridge, Ontario 2001; Nicholson, H (trans.) (1997) Chronicle of the Third Crusade: A Translation of the Itinerarium Peregrinorum et Gesta Regis Ricardi, Ashgate;ed. W. Stubbs 1864; ed. M. T. Stead 1920

- Baha al-Din ibn Shaddad's Rare and Excellent History of Saladin (his name is also rendered Beha al-Din and Beha Ed-Din), trans. C. W. Wilson (1897) Saladin Or What Befell Sultan Yusuf, Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society, London.[1]

Secondary sources

[edit]- Bennett, Matthew. (1996) The Cambridge Illustrated Atlas of Warfare: The Middle Ages, 768–1487, Vol 1., Cambridge University Press

- Bennett, Stephen. (2017), The Battle of Arsuf/Arsur, A Reappraisal of the Charge of the Hospitallers. The Military Orders Volume 6.1 Culture and Conflict in the Mediterranean World. Abingdon, UK: Routledge, pp. 44–53.

- Bennett, Stephen (2021). Elite Participation in the Third Crusade. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1783275786.

- Boas, Adrian (ed.) (2015) The Crusader World, Routledge, ISBN 9781315684154

- Gillingham, John (1978). Richard the Lionheart. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-77453-0.

- Lev, Y. (1997) War and Society in the Eastern Mediterranean 7th–15th Centuries. Leiden.

- Möhring, Hannes (2009). "Die muslimische Strategie der Schleifung fränkischen Festungen und Städte in der Levante". Burgen und Schlösser: Zeitschrift für Burgenforschung und Denkmalpflege (in German). 50 (4): 211–217. doi:10.11588/BUS.2009.4.48565.

- Nicholson, H. J. (ed.)(1997), The Chronicle of the Third Crusade: The Itinerarium Peregrinorum et Gesta Regis Ricardi, Ashgate.

- Oman, Charles William Chadwick. (1924) A History of the Art of War in the Middle Ages Vol. I, 378–1278 AD. London: Greenhill Books; Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books, reprinted in 1998.

- Parry, V. J. & Yapp, M. E. (1975) War, Technology and Society in the Middle East.

- Runciman, S. (reprinted 1987) A History of the Crusades: Volume III, The Kingdom of Acre and the Later Crusades, Cambridge University Press Archive.

- Smail, R. C. (1995) [1956]. Crusading Warfare, 1097–1193 (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 162–165. ISBN 0-521-48029-9.

- Sweeney, J. R. (1981) Hungary in the Crusades, 1169–1218. The International History Review 3.

- Verbruggen, J. F. (1997) The Art of Warfare in Western Europe During the Middle Ages: From the Eighth Century to 1340. Boydell & Brewer.

- van Werveke, H. (1972) The Contribution of Hainaut and Flanders in the Third Crusade. Le Moyen Age 78.

Further reading

[edit]- DeVries, Kelly (2006). Battles of the Medieval World. New York: Barnes & Noble. ISBN 0-7607-7779-9.

- Evans, Mark (August 2001). "Battle of Arsuf: Climactic Clash of the Cross and Crescent". Military History.

- Nicolle, David (2005). The Third Crusade 1191: Richard the Lionheart and the Battle for Jerusalem. Osprey Campaign. Vol. 161. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-868-5.

- Nicolle, David (26 March 1986). Saladin and the Saracens. London: Osprey. ISBN 0-85045-682-7.

- Conflicts in 1191

- 1191 in Asia

- Battles of the Third Crusade

- Battles involving England

- Battles involving France

- Battles involving the Kingdom of Jerusalem

- Battles involving the Ayyubids

- Battles involving the Knights Hospitaller

- Battles involving the Knights Templar

- Battles of Saladin

- 1190s in the Kingdom of Jerusalem

- 1190s in the Ayyubid Sultanate

- Richard I of England