Jack Kevorkian

Jack Kevorkian | |

|---|---|

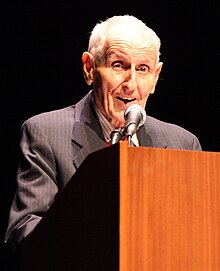

Kevorkian in 1996 | |

| Born | Murad Jacob Kevorkian[1] May 26, 1928 Pontiac, Michigan, U.S. |

| Died | June 3, 2011 (aged 83) Royal Oak, Michigan, U.S. |

| Education | University of Michigan |

| Occupation | Pathologist |

| Years active | 1952–2011 |

| Medical career | |

| Institutions | |

| Sub-specialties | Euthanasia medicine |

Murad Jacob "Jack" Kevorkian (May 26, 1928 – June 3, 2011) was an American pathologist and euthanasia proponent. He publicly championed a terminal patient's right to die by physician-assisted suicide, embodied in his quote, "Dying is not a crime".[2] Kevorkian said that he assisted at least 130 patients to that end. He was convicted of murder in 1999 and was often portrayed in the media with the name of "Dr. Death".[3]

In 1998, Kevorkian was arrested and tried for his role in the voluntary euthanasia of a man named Thomas Youk who had Lou Gehrig's disease, or ALS. He was convicted of second-degree murder and served eight years of a 10-to-25-year prison sentence. He was released on parole on June 1, 2007, on condition he would not offer advice about, participate in, or be present at the act of any type of euthanasia to any other person, nor that he promote or talk about the procedure of assisted suicide.[4]

Early life and education

[edit]Murad Jacob Kevorkian (Armenian: մւրադ ձածոբ կեվորկիան) was born in Pontiac, Michigan, on May 26, 1928,[1][5] to Armenian immigrants from the Ottoman Empire, in what is now Turkey. His father, Levon (1891–1960), was born in the village of Passen, near Erzurum, and his mother, Satenig (1900–1968), was born in the village of Govdun, near Sivas.[6][7] His father left Ottoman Armenia and made his way to Pontiac in 1912, where he found work at an automobile foundry. Satenig fled the Armenian genocide of 1915, finding refuge with relatives in Paris and eventually reuniting with her brother in Pontiac. Levon and Satenig met through the Armenian community in their city, where they married and began their family. The couple had a daughter, Margaret, in 1926, followed by son Murad, and their third and last child, Flora.[8]

When Kevorkian was a child, his parents took him to an Orthodox church weekly.[9] He started questioning the existence of a God, as he believed an all-knowing God would have prevented the Armenian Genocide on his extended family. He stopped attending church by the time he was 12.[10]

Kevorkian was a child prodigy, teaching himself multiple languages (including German, Russian, Greek, and Japanese).[11] As such, he was often alienated by his peers.[12] Kevorkian graduated from Pontiac Central High School with honors in 1945, at the age of 17. In 1952, he graduated from the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor.[13][14][15]

Kevorkian completed residency training in anatomical and clinical pathology and briefly conducted research on blood transfusion.[16]

Career

[edit]

Over a period of decades, Kevorkian developed several controversial ideas related to death. In a 1959 journal article, he wrote:

I propose that a prisoner condemned to death by due process of law be allowed to submit, by his own free choice, to medical experimentation under complete anaesthesia (at the time appointed for administering the penalty) as a form of execution in lieu of conventional methods prescribed by law.[17]

Senior doctors at the University of Michigan, Kevorkian's employer, opposed his proposal and Kevorkian chose to leave the university rather than stop advocating his ideas. Ultimately, he gained little support for his plan. He returned to the idea of using death-row inmates for medical purposes after the Supreme Court's 1976 decision in Gregg v. Georgia reinstituted the death penalty. He advocated harvesting the organs from inmates after the death penalty was carried out for transplant into sick patients, but he failed to gain the cooperation of prison officials.[18]

As a pathologist at Pontiac General Hospital, Kevorkian experimented with transfusing blood from the recently deceased into live patients. He drew blood from corpses recently brought into the hospital and transferred it successfully into the bodies of hospital staff members. Kevorkian thought that the U.S. military might be interested in using this technique to help wounded soldiers during a battle, but the Pentagon was not interested.[18]

In the 1980s, Kevorkian wrote a series of articles for the German journal Medicine and Law that laid out his thinking on the ethics of euthanasia.[13][19]

In 1987, Kevorkian started advertising in Detroit newspapers as a physician consultant for "death counseling". His first public assisted suicide, of Janet Adkins, a 54-year-old woman diagnosed in 1989 with Alzheimer's disease, took place in 1990. Charges of murder were dropped on December 13, 1990, as there were, at that time, no laws in Michigan regarding assisted suicide.[20] In 1991, however, the State of Michigan revoked Kevorkian's medical license and made it clear that, given his actions, he was no longer permitted to practice medicine or to work with patients.[21] His California medical license was suspended in April 1993 by an administrative law judge, with Kevorkian's attorney responding that Kevorkian "will go on assisting people commit suicide. He dares that California judge to come catch him".[22]

According to his lawyer Geoffrey Fieger, Kevorkian assisted in the deaths of 130 terminally ill people between 1990 and 1998. In each of these cases, the individuals themselves allegedly took the final action which resulted in their own deaths. Kevorkian allegedly assisted only by attaching the individual to a euthanasia device that he had devised and constructed. The individual then pushed a button which released the drugs or chemicals that would end their own life. Two deaths were assisted by means of a device which delivered the euthanizing drugs intravenously. Kevorkian called the device a "Thanatron" ("Death machine", from the Greek thanatos meaning "death").[23] Other people were assisted by a device which employed a gas mask fed by a canister of carbon monoxide, which Kevorkian called the "Mercitron" ("Mercy machine").[24]

Criticism and Kevorkian's response

[edit]My aim in helping the patient was not to cause death. My aim was to end suffering. It's got to be decriminalized.

According to a report by the Detroit Free Press, 60% of the patients who died with Kevorkian's help were not terminally ill, and at least 13 had not complained of pain. The report further asserted that Kevorkian's counseling was too brief (with at least 19 patients dying less than 24 hours after first meeting Kevorkian) and lacked a psychiatric exam in at least 19 cases, 5 of which involved people with histories of depression, though Kevorkian was sometimes alerted that the patient was unhappy for reasons other than their medical condition. In 1992, Kevorkian himself wrote that it is always necessary to consult a psychiatrist when performing assisted suicides because a person's "mental state is [...] of paramount importance."[26] The report also stated that Kevorkian failed to refer at least 17 patients to a pain specialist after they complained of chronic pain and sometimes failed to obtain a complete medical record for his patients, with at least three autopsies of suicides Kevorkian had assisted with showing the person who committed suicide to have no physical sign of disease. Rebecca Badger, a patient of Kevorkian's and a mentally troubled drug abuser, had been mistakenly diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. The report also stated that Janet Adkins, Kevorkian's first euthanasia patient, had been chosen without Kevorkian ever speaking to her, only with her husband, and that when Kevorkian first met Adkins two days before her assisted suicide he "made no real effort to discover whether Ms. Adkins wished to end her life," as the Michigan Court of Appeals put it in a 1995 ruling upholding an order against Kevorkian's activity.[26] According to The Economist: "Studies of those who sought out Dr. Kevorkian, however, suggest that though many had a worsening illness... it was not usually terminal. Autopsies showed five people had no disease at all... Little over a third were in pain. Some presumably suffered from no more than hypochondria or depression."[27]

In response, Kevorkian's attorney Geoffrey Fieger published an essay stating, "I've never met any doctor who lived by such exacting guidelines as Kevorkian... [H]e published them in an article for the American Journal of Forensic Psychiatry in 1992. Last year he got a committee of doctors, the Physicians of Mercy, to lay down new guidelines, which he scrupulously follows."[26] However, Fieger stated that Kevorkian found it difficult to follow his "exacting guidelines" because of "persecution and prosecution", adding, "[H]e's proposed these guidelines saying this is what ought to be done. These are not to be done in times of war, and we're at war."[26]

In a 2010 interview with Sanjay Gupta, Kevorkian stated an objection to the status of assisted suicide in Oregon, Washington, and Montana. At that time, only in those three states was assisted suicide legal in the United States, and then only for terminally ill patients. To Gupta, Kevorkian stated, "What difference does it make if someone is terminal? We are all terminal."[28] In his view, a patient had to be suffering but did not have to be terminally ill to be assisted in committing suicide. However, he also said in that same interview that he declined four out of every five assisted suicide requests, on the grounds that the patient needed more treatment or medical records had to be checked.[29]

In 2011, disability rights and anti-legalization of assisted suicide and euthanasia group Not Dead Yet spoke out against Kevorkian, citing potentially concerning sentiments he expressed in his published writing.[30] On page 214 of Prescription: Medicide, the Goodness of Planned Death, Kevorkian wrote that assisting "suffering or doomed persons [to] kill themselves" was "merely the first step, an early distasteful professional obligation... What I find most satisfying is the prospect of making possible the performance of invaluable experiments or other beneficial medical acts under conditions that this first unpleasant step can help establish – in a [portmanteau] word obitiatry." In a journal article titled "The Last Fearsome Taboo: Medical Aspects of Planned Death", Kevorkian also detailed anesthetizing, experimenting on, and utilizing the organs of a disabled newborn as a token of "daring and highly imaginative research" that would be possible "beyond the constraints of traditional but outmoded, hopelessly inadequate, and essentially irrelevant ethical codes now sustained for the most part by vacuous sentimental reverence".

Art and music

[edit]

Kevorkian was a jazz musician and composer. The Kevorkian Suite: A Very Still Life was a 1997 limited-release CD of 5,000 copies from the 'Lucid Subjazz' label. It features Kevorkian on the flute and organ playing his own works with "The Morpheus Quintet". It was reviewed in Entertainment Weekly online as "weird" but "good-natured".[31] As of 1997, 1,400 units had been sold.[31] Kevorkian wrote all the songs but one; the album was reviewed in jazzreview.com as "very much grooviness" except for one tune, with "stuff in between that's worthy of multiple spins".[32]

The first public performance of the complete classical organ works by Jack Kevorkian was by Craig Rifel in a live concert[33] on April 30, 1996, at Central United Methodist Church in Waterford, Michigan, including Kevorkian's Prelude & Fugue in E-flat, Pipe Dream, Sonata in D, Passacaglia on B-A-C-H, Pastorale & Fugue in B-Flat, and Fantasy & Fugue in C. In 1999, the Geneva-based self-determination society EXIT commissioned David Woodard to orchestrate wind settings of Kevorkian's organ works.[34]

He was also an oil painter. His work tended toward the grotesque and surreal, and he had created pieces of symbolic art, such as one "of a child eating the flesh off a decomposing corpse".[19] Of his known works, six were made available in the 1990s for print release. The Ariana Gallery in Royal Oak, Michigan, is the exclusive distributor of Kevorkian's artwork. The original oil prints are not for release.[35] Sludge metal band Acid Bath used his painting "For He is Raised" as the cover art for their 1996 album Paegan Terrorism Tactics.[36]

In 2011, his paintings became the center of a legal entanglement between his sole heir and the Armenian Library and Museum of America.[37]

Trials, conviction, and imprisonment

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Euthanasia |

|---|

| Types |

| Views |

| Groups |

| People |

| Books |

| Jurisdictions |

| Laws |

| Alternatives |

| Other issues |

Kevorkian was tried four times for assisting suicides between May 1994 and June 1997. With the assistance of Fieger, Kevorkian was acquitted three times. The fourth trial ended in a mistrial.[1] The trials helped Kevorkian gain public support for his cause. After Oakland County prosecutor Richard Thompson lost a primary election to a Republican challenger,[38] Thompson attributed the loss in part to the declining public support for the prosecution of Kevorkian and its associated legal expenses.[39]

In the November 22, 1998, broadcast of CBS News' 60 Minutes, Kevorkian allowed the airing of a videotape he made on September 17, 1998, which depicted the voluntary euthanasia of Thomas Youk, 52, who was in the final stages of Lou Gehrig's disease. After Youk provided his fully informed consent (a sometimes complex legal determination made in this case by editorial consensus) on September 17, 1998, Kevorkian himself administered Thomas Youk a lethal injection. This was highly significant, as all of his earlier clients had reportedly completed the process themselves. During the videotape, Kevorkian dared the authorities to try to convict him or stop him from carrying out mercy killings. Youk's family described the lethal injection as humane, not murder.

On November 25, 1998, Kevorkian was charged with second-degree murder and the delivery of a controlled substance (administering the lethal injection to Thomas Youk).[13] Because Kevorkian's license to practice medicine had been revoked eight years previously, he was not legally allowed to possess the controlled substance.

On March 26, 1999, a jury began deliberations in the first-degree murder trial of Kevorkian.[40] He had discharged his attorneys and proceeded through the trial representing himself, a decision he later regretted.[1] The judge ordered a criminal defense attorney to remain available at trial as standby counsel for information and advice. Inexperienced in law but persisting in his efforts to represent himself, Kevorkian encountered great difficulty in presenting his evidence and arguments. He was not able to call any witnesses to the stand as the judge did not deem the testimony of any of his witnesses relevant.[41]

After a two-day trial, the Michigan jury found Kevorkian guilty of second-degree homicide.[1] Judge Jessica Cooper sentenced Kevorkian to serve 10–25 years in prison and told him:

This is a court of law and you said you invited yourself here to take a final stand. But this trial was not an opportunity for a referendum. The law prohibiting euthanasia was specifically reviewed and clarified by the Michigan Supreme Court several years ago in a decision involving your very own cases, sir. So the charge here should come as no surprise to you. You invited yourself to the wrong forum. Well, we are a nation of laws, and we are a nation that tolerates differences of opinion because we have a civilized and a nonviolent way of resolving our conflicts that weighs the law and adheres to the law. We have the means and the methods to protest the laws with which we disagree. You can criticize the law, you can write or lecture about the law, you can speak to the media or petition the voters.

Kevorkian was sent to a prison in Coldwater, Michigan, to serve his sentence.[42] After his conviction (and subsequent losses on appeal), Kevorkian was denied parole repeatedly until 2007.[43]

In an MSNBC interview aired on September 29, 2005, Kevorkian said that if he were granted parole, he would not resume directly helping people die and would restrict himself to campaigning to have the law changed. On December 22, 2005, Kevorkian was denied parole by a board on the count of 7–2 recommending not to give parole.[44]

Reportedly terminally ill with Hepatitis C, which he contracted in the 1960s, Kevorkian was expected to die within a year in May 2006.[45] After applying for a pardon, parole, or commutation by the parole board and Governor Jennifer Granholm, he was paroled for good behavior on June 1, 2007. He had spent eight years and two and a half months in prison.[46][47]

Kevorkian was on parole for two years, under the conditions that he would not help anyone else die, or provide care for anyone older than 62 or disabled.[48] Kevorkian said he would abstain from assisting any more terminal patients with death, and his role in the matter would strictly be to persuade states to change their laws on assisted suicide. He was also forbidden by the rules of his parole from commenting about assisted suicide procedure.[49][50]

Activities after his release from prison

[edit]

Kevorkian gave a number of lectures upon his release. He lectured at universities such as the University of Florida,[51] Nova Southeastern University,[52] and the University of California, Los Angeles.[53] His lectures were not limited to the topic of euthanasia; he also discussed such topics as tyranny, the criminal justice system, politics, the Ninth Amendment to the United States Constitution and Armenian culture. He appeared on the Fox News Channel's Your World with Neil Cavuto on September 2, 2009, to discuss health care reform.

On April 15 and 16, 2010, Kevorkian appeared on CNN's Anderson Cooper 360°.[54] Cooper asked, "You are saying doctors play God all the time?" Kevorkian said: "Of course. Any time you interfere with a natural process, you are playing God."[55] Director Barry Levinson and actors Al Pacino, Susan Sarandon and John Goodman, who appeared in You Don't Know Jack, a film based on Kevorkian's life, were interviewed alongside Kevorkian. Kevorkian was again interviewed by Cavuto on Your World on April 19, 2010, regarding the movie and Kevorkian's world view. You Don't Know Jack premiered April 24, 2010, on HBO.[56] The film premiered April 14 at the Ziegfeld Theater in New York City. Kevorkian walked the red carpet alongside Al Pacino, who portrayed him in the film.[57] Pacino received Emmy and Golden Globe awards for his portrayal and personally thanked Kevorkian, who was in the audience, upon receiving both of these awards. Kevorkian stated that the film "brings tears to my eyes – and I lived through it".[58]

2008 congressional race

[edit]On March 12, 2008, Kevorkian announced plans to run for United States Congress to represent Michigan's 9th congressional district as an independent against eight-term congressman Joe Knollenberg (R-Bloomfield Hills), former Michigan Lottery commissioner and state senator Gary Peters (D-Bloomfield Township), Adam Goodman (L-Royal Oak) and Douglas Campbell (G-Ferndale). The race had already garnered national attention due to Democrats targeting the historically Republican district based in Oakland County, which Knollenberg barely won in 2006 against a little-known opponent. The district would suffer some of the worst brunt of the Great Recession due to declines in Detroit's automotive industry. Upon Kevorkian's entry into the race, one analyst viewed him as a potential spoiler to Peters' candidacy.[59]

Ultimately, Kevorkian received 8,987 votes (2.6% of the vote) in the election, in which Peters defeated the incumbent Knollenberg by a nine-percent margin.[60] Peters would eventually serve three terms in Congress before making a successful run for the United States Senate.

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Gary Peters | 183,311 | 52.1 | +5.9 | |

| Republican | Joe Knollenberg (i) | 150,035 | 42.6 | −9.0 | |

| Independent | Jack Kevorkian | 8,987 | 2.6 | N/A | |

| Libertarian | Adam Goodman | 4,893 | 1.4 | −0.1 | |

| Green | Douglas Campbell | 4,737 | 1.3 | +0.4 | |

| Democratic gain from Republican | Swing | ||||

Illness and death

[edit]Kevorkian had struggled with kidney problems for years.[62] He was diagnosed with liver cancer, which "may have been caused by hepatitis C," according to his longtime friend Neal Nicol.[45] Kevorkian was hospitalized on May 18, 2011, with kidney problems and pneumonia.[1] Kevorkian's condition grew rapidly worse and he died from a thrombosis on June 3, 2011, eight days after his 83rd birthday, at William Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, Michigan.[1][5] According to his attorney, Mayer Morganroth, there were no artificial attempts to keep him alive and his death was painless.[45] Kevorkian was buried in White Chapel Memorial Cemetery in Troy, Michigan.[63]

Legacy

[edit]Judge Thomas Jackson, who presided over Kevorkian's first murder trial in 1994, commented that he wanted to express sorrow at Kevorkian's death and that the 1994 case was brought under "a badly written law" aimed at Kevorkian, but he attempted to give him "the best trial possible". Geoffrey Fieger, Kevorkian's lawyer during the 1990s, gave a speech at a press conference in which he stated: "Dr. Jack Kevorkian didn't seek out history, but he made history."[64] Fieger said that Kevorkian revolutionized the concept of suicide by working to help people end their own suffering, because he believed physicians are responsible for alleviating the suffering of patients, even if that meant allowing patients to die.[64]

Kevorkian spoke at Presbyterian and Episcopal churches to gain support for euthanasia.[65][66] John Finn, medical director of palliative care at the Catholic[67] St. John's Hospital, said Kevorkian's methods were unorthodox and inappropriate. He added that many of Kevorkian's patients were isolated, lonely, and potentially depressed, and therefore in no state to mindfully choose whether to live or die.[64] Derek Humphry, author of the suicide handbook Final Exit, said Kevorkian was "too obsessed, too fanatical, in his interest in death and suicide to offer direction for the nation".[68]

In a 2015 Retro Report story about Kevorkian's legacy and the Right to Die movement, journalist Jack Lessenberry said Kevorkian "got a national debate going, which I think he then helped stifle by his own outrageous actions".[69] Howard Markel, a medical historian at the University of Michigan, said that Kevorkian "was a major historical figure in modern medicine".[64] The Catholic Church in Detroit said Kevorkian left behind a "deadly legacy" that denied scores of people their right to "dignified, natural" deaths.[70] Philip Nitschke, founder and director of right-to-die organization Exit International, said that Kevorkian "moved the debate forward in ways the rest of us can only imagine. He started at a time when it was hardly talked about and got people thinking about the issue. He paid one hell of a price, and that is one of the hallmarks of true heroism."[71]

The epitaph on Kevorkian's tombstone reads, "He sacrificed himself for everyone's rights."

In 2015, the 1968 Volkswagen Type 2 van in which Jack Kevorkian assisted some of his suicidal patients was bought by paranormal investigator Zak Bagans (from the documentary series Ghost Adventures) for display in his haunted museum in Las Vegas.[72]

Publications

[edit]Books

[edit]- Kevorkian, Jack (1959). The Story of Dissection. Philosophical Library. ISBN 978-1-258-07746-4.

- Kevorkian, Jack (1960). Medical Research and the Death Penalty: A Dialogue. Vantage Books. ISBN 978-0-9602030-1-7.

- Kevorkian, Jack (1966). Beyond Any Kind of God. Philosophical Library. ISBN 978-0-8022-0847-7.†

- Kevorkian, Jack (1978). Slimmericks and the Demi-Diet. Penumbra, Inc. ISBN 978-0-9602030-0-0.††

- Kevorkian, Jack (1991). Prescription: Medicide, the Goodness of Planned Death. Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-0-87975-872-1 – via Internet Archive.

- Kevorkian, Jack (2004). glimmerIQs. Penumbra, Inc. ISBN 978-0-9602030-7-9.

- Kevorkian, Jack (2005). Amendment IX: Our Cornucopia of Rights. Penumbra, Inc. ISBN 096020301X.

- Kevorkian, Jack (2010). When the People Bubble POPs. World Audience, Inc. ISBN 978-1-935444-91-6.

† = Later heavily revised and incorporated into glimmerIQs

†† = Later incorporated in abridged form into glimmerIQs

* = Revised and distributed in 2009 by World Audience, Inc.

Selected journal articles

[edit]- Kevorkian J (1985). "Opinions on capital punishment, executions and medical science". Medicine and Law. 4 (6): 515–533. PMID 4094526.

- Kevorkian J (1987). "Capital punishment and organ retrieval". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 136 (12): 1240. PMC 1492232. PMID 3580984.

- Kevorkian J (1988). "The last fearsome taboo: Medical aspects of planned death". Medicine and Law. 7 (1): 1–14. PMID 3277000.

- Kevorkian J (1989). "Marketing of human organs and tissues is justified and necessary". Medicine and Law. 7 (6): 557–565. PMID 2495395.

In culture

[edit]- You Don't Know Jack, 2010 film about Jack Kevorkian

- Paegan Terrorism Tactics, a 1996 album by Acid Bath, features a painting by Kevorkian for the cover art[73]

- Kevorkian is referenced in the Seinfeld episode "The Suicide".

See also

[edit]- God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian, a collection of short fictional interviews written by Kurt Vonnegut

- You Don't Know Jack, a 2010 television film

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Schneider, Keith (June 3, 2011). "Dr. Jack Kevorkian Dies at 83; A Doctor Who Helped End Lives". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ Wells, Samuel; Quash, Ben (2010). Introducing Christian Ethics. John Wiley and Sons. p. 329. ISBN 978-1-4051-5276-1.

- ^ Roberts J, Kjellstrand C (June 8, 1996). "Jack Kevorkian: a medical hero". BMJ. 312 (7044): 1434. doi:10.1136/bmj.312.7044.1434. PMC 2351178. PMID 8664610.

- ^ Monica Davey. "Kevorkian Speaks After His Release From Prison" Archived September 4, 2024, at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times. June 4, 2007.

- ^ a b "Jacob 'Jack' Kevorkian Dies; Death With Dignity Proponent Remembered". June 4, 2011. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- ^ "BHL: Jack Kevorkian papers". Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ^ Kevorkian, Jack (2009). glimmerIQs (Paperback). World Audience, Inc. ISBN 978-1-935444-88-6.

- ^ Kevorkian, Jack (December 15, 2010). "Biography". www.thekevorkianpapers.com/. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- ^ Warrick, Pamela (December 6, 1992). "Suicide's Partner : Is Jack Kevorkian an angel of mercy, or is he a killer, as some critics charge? 'Society is making me Dr. Death,' he says. 'Why can't they see? I'm Dr. Life!'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 5, 2023. Retrieved January 28, 2022.

- ^ "Jack Kevorkian | Biography". May 20, 2021. Archived from the original on January 5, 2023. Retrieved August 21, 2022.

- ^ "Jack Kevorkian: How he made controversial history". BBC News. June 3, 2011. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ^ Read Between the Dying and the Dead Online by Neal Nicol and Harry L. Wylie | Books. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ^ a b c "The Kevorian Verdict: A Chronology". Frontline. May 1996. Archived from the original on June 20, 2021. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- ^ Chermak, Steven M.; Bailey, Frankie Y. (2007). Crimes and Trials of the Century. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 101–102. ISBN 978-0-313-34110-6.

- ^ Azadian, Edmond Y.; Hacikyan, Agop J.; Franchuk, Edward S. (1999). History on the move: views, interviews and essays on Armenian issues. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. p. 233. ISBN 0-8143-2916-0. Archived from the original on September 4, 2024. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Jack Kevorkian Biography". Biography.com. 2012. Archived from the original on October 28, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- ^ Kevorkian, Jack (May–June 1959). "Capital Punishment or Capital Gain". The Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology, and Police Science. 50 (1): 50–51.

- ^ a b Betzold, Michael (September 19, 1993). "1993: Excerpt from 'Appointment with Doctor Death'". Detroit Free Press. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- ^ a b Lessenberry, Jack (July 1994). "Death becomes him". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on August 6, 2003. Retrieved July 11, 2010 – via PBS.org.

- ^ "People v. Kevorkian; Hobbins v. Attorney General". Ascension Health. 1994. Archived from the original on September 8, 2003. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ^ "Kevorkian medical license revoked". Lodi News-Sentinel. Michigan. Associated Press. November 21, 1991. p. 8. Archived from the original on April 26, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ Granberry, Michael (April 28, 1993). "State Suspends Kevorkian's Medical License". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 29, 2024. Retrieved March 25, 2024.

- ^ "The Kevorkian Verdict: The Thanatron". PBS. Frontline. May 1996. Archived from the original on July 28, 2018. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- ^ Jackson, Nicholas (June 3, 2011). "Jack Kevorkian's Death Van and the Tech of Assisted Suicide". The Atlantic Monthly. TheAtlantic.com. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- ^ "Jacob 'Jack' Kevorkian Dies; Death With Dignity Proponent Remembered". medicalnewstoday.com. 2011. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Cheyfitz, Kirk (March 3, 1997). "Suicide Machine, Part 1: Kevorkian rushes to fulfill his clients' desire to die" Archived June 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Detroit Free Press. Archived May 26, 2007.

- ^ "Jack Kevorkian, champion of voluntary euthanasia, died on June 3rd, aged 83". The Economist. webCitation.org. June 9, 2011. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011.

- ^ "Kevorian: "I have no regrets"". CNN. June 14, 2010. Archived from the original on July 10, 2010. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ "'Dr. Death's' view on life". CNN. June 14, 2010. Archived from the original on December 30, 2010. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ "A little bit about the REAL Jack Kevorkian – In His Own Words". June 7, 2011. Archived from the original on August 13, 2016. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

- ^ a b Essex, Andrew (December 26, 1997). "Death Mettle" Archived August 15, 2022, at the Wayback Machine . Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ "Featured Artist: Jack Kevorkian and Morpheus Quintet – CD Title: A Very Still Life" Archived December 20, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. JazzReview.com.

- ^ Productions, Primeau (March 29, 2012). "Jack Kevorkian Performs in Concert – Waterford Michigan 1996". Archived from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved July 24, 2017 – via Vimeo.

- ^ Woodard, D., "Musica letitiae comes medicina dolorum", trans. S. Zeitz, Der Freund, Nr. 7, March 2006, pp. 34–41.

- ^ "The Kevorkian Verdict: The Ariana Gallery". PBS (Press release). Frontline. May 1996. Archived from the original on March 13, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- ^ "Acid Bath – Paegan Terrorism Tactics Remastered, Reissued". Brave Words. August 10, 2010. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ "Kevorkian Estate To Auction Disputed Paintings". WDIV-TV. ClickonDetroit.com. November 2, 2011. Archived from the original on January 30, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- ^ "Prosecutor has last shot at Dr. Death". Sun Journal. Lewiston Maine. November 1, 1996. p. 3A. Archived from the original on May 31, 2021. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- ^ Davis, Robert (August 8, 1996). "Assisted Suicide". USA Today. p. 3A. Archived from the original on June 24, 2012. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

Thompson, the first Oakland County prosecutor in 24 years to lose an election, agreed that the controversy clearly was an issue in his defeat.

- ^ Claiborne, William (March 26, 1999). "Kevorkian, Arguing Own Defense, Asks Jury to Disregard Law". Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 10, 2023. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- ^ Williams, Marie Higgins (2000). "Pro Se Criminal Defendant, Standby Counsel, and the Judge: A Proposal for Better-Defined Roles, The". 71 U. Colo. L. Rev. p. 789. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ Jessica Cooper (April 14, 1999). "Statement from Judge to Kevorkian". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 24, 2017. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ Egan, Paul (December 14, 2006). "After 8 years, Kevorkian to go free". The Detroit News. Detnews.com. Archived from the original on August 4, 2010. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- ^ Rita Cosby (September 29, 2005). "'Dr. Death' speaks out from jail". NBC News. Archived from the original on September 28, 2023. Retrieved August 3, 2024.

- ^ a b c Joe Swickard; Pat Anstett (June 3, 2011). "Assisted suicide advocate Jack Kevorkian dies". Detroit Free Press. Freep.com. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011.

- ^ "Jack Kevorkian Plans Run For Congress". CBS News. cbsnews.com. AP. March 12, 2008. Archived from the original on December 22, 2019. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ Lara Setrakian (June 1, 2007). "Dying 'Dr. Death' Has Second Thoughts About Assisting Suicides". ABC News. Archived from the original on December 8, 2010. Retrieved June 16, 2009.

- ^ "Kevorkian released from prison after 8 years". NBC News. June 1, 2007. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2009.

- ^ "Kevorkian criticizes attack on right-to-die group". mlive.com. Michigan Live. AP. February 27, 2009.

- ^ "Four arrested in 2 states in assisted-suicide probe". CNN. February 26, 2009. Archived from the original on March 30, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- ^ Stripling, Jack (January 16, 2008). "Kevorkian pushes for euthanasia". Gainesville Sun. Archived from the original on April 26, 2010. Retrieved June 16, 2009.

- ^ Ba Tran, Andrew (February 5, 2009). "Jack Kevorkian unveils U.S. flag altered with swastika". Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on September 17, 2009. Retrieved October 30, 2009.

- ^ Strutner, Suzy (January 11, 2011). "Right-to-die activist Dr. Jack Kevorkian will share his ideology of death and story of life during Royce Hall lecture". Daily Bruin. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- ^ "Video: Mr. Kevorkian on physician-assisted suicide". Anderson Cooper 360. CNN. April 15, 2010. Archived from the original (Flash video) on April 21, 2010. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ^ "Mr. Kevorkian Responds to Question about Playing God". Anderson Cooper 360. CNN. April 16, 2010. Archived from the original (Flash video) on April 23, 2010. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ^ "You Don't Know Jack" (Flash site). HBO. 2010. Archived from the original on October 14, 2017. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ^ "Premiere of You Don't Know Jack at Ziegfeld Theatre". Day Life.com (Getty Images). April 14, 2010. Archived from the original (Image gallery) on July 25, 2010. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ^ Tara Krieger (November 2, 2010). "A New Life for Dr. Death". Archived from the original on April 24, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- ^ "Kevorkian plans congressional run". msnbc.com. March 13, 2008. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- ^ "Official Michigan General Candidate Listing". Michigan Department of State. November 25, 2008. Archived from the original on April 16, 2020. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ "2008 Unofficial Michigan General Election Results – 9th District Representative in Congress 2 Year Term (1) Position". Archived from the original on November 7, 2008.

- ^ "Dr. Jack Kevorkian dead at 83". CNN. June 3, 2011. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ^ "With video: Politicians, officials and residents remember Kevorkian". Detroit Free Press. Freep.com. June 3, 2011. Archived from the original on June 8, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Brienne Prusak (June 2011). "'U' Medical School alum Dr. Kevorkian dies at 83". The Michigan Daily. Archived from the original on June 15, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ^ "Dr. Death asks parishioners for help in assisted suicide campaign". UPI. Retrieved January 28, 2022.

- ^ "Kevorkian Pleads For Legalization Of Assisted Suicide". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ "Mission and Values, St. John Health, as a Catholic health ministry". stjohnprovidence.org. 2011. Archived from the original on August 17, 2011. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ^ Joe Swickard; Patricia Anstett; L.L. Brasier (June 4, 2011). "Jack Kevorkian sparked a debate on death". Detroit Free Press. Freep.com. Archived from the original on September 15, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- ^ Wilson, Sianne. "A Right to Die?". www.RetroReport.org. Retro Report. Archived from the original on February 1, 2016. Retrieved July 30, 2015.

- ^ Niraj Warikoo. "Archdiocese of Detroit: Kevorkian leaves 'deadly legacy'". Detroit Free Press. Freep.com. Archived from the original on August 8, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- ^ Donaldson James, Susan (June 23, 2011). "Jack Kevorkian, Godfather of Right-to Die-Movement, Dies Leaving Controversial Legacy". ABC News. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- ^ "Infamous Kevorkian van sold to ghost hunter". Archived from the original on September 9, 2020. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ "CoC : Acid Bath - Paegan Terrorism Tactics : Review". www.chroniclesofchaos.com. Retrieved November 15, 2024.

External links

[edit]- Jack Kevorkian collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- A Right to Die? a documentary from Retro Report

- "Papa" Prell Radio interview with Kevorkian. (MP3, 15 minutes). Prell archive at Radio Horror Hosts website.

- "Court TV Case Files – Trial coverage". CourtTV.com. Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- "The Kevorkian Verdict: The Life and Legacy of the Suicide Doctor" Frontline; PBS.org – with timeline and other info.

- Kevorkian's Art Work Frontline; PBS.org.

- "Unsung American-Armenian Hero Kevorkian Coming Home To Die". James Donahue website. tripod.com. May 2007. Archived from the original on June 8, 2007.

- Kevorkian on law and the constitution during an appearance at Harvard Law School (Harvard Law Record)

- Michigan Department of Corrections record for Jack Kevorkian Archived January 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Jack Kevorkian at Find a Grave

- 20th-century American criminals

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American non-fiction writers

- 20th-century American physicians

- 21st-century American male writers

- 21st-century American non-fiction writers

- American critics of religions

- American male criminals

- American medical writers

- American pathologists

- American people convicted of murder

- American people of Armenian descent

- American political candidates

- Assisted suicide in the United States

- Candidates in the 2008 United States elections

- Criminals from Michigan

- Deaths from kidney failure in the United States

- Deaths from thrombosis

- Euthanasia activists

- Euthanasia doctors

- Euthanasia in the United States

- Medical practitioners convicted of murdering their patients

- Michigan independents

- Multilingual writers

- People convicted of murder by Michigan

- People from Pontiac, Michigan

- People involved with death and dying

- Physicians from Michigan

- University of Michigan Medical School alumni

- Writers from Michigan

- 1928 births

- 2011 deaths